Build a Blog: Deploy Azure Infrastructure three ways

For most developers, dealing with the infrastructure part of the job is hard. I like to say “give me a database and a web site” and prefer not to get into the other requirements. My web sites and other cloud projects (including this one) are pretty open. So, what’s the minimum I need to know to deploy stuff on Azure?

This post is part of a sequence showing how to deploy a blog on Azure Static Web Apps:

- Deploying Azure Static Web Apps

- Configuring Azure DNS

- Configuring Static Web Apps Custom Domains

- Taking Static Web Apps to Production

Today, I’m going to look at three ways to deploy the same thing. That “thing” is an Azure Static Web App - the same one that is used to host this web site. I’ll look at the techniques and why it is better (or worse) than the others.

Three ways? Surely, there are more than that! Why, yes. There are. You can use any number of infrastructure as code (IaC) tools, and there are lots of opinions on how to lay out an infrastructure for enterprise use (which I promise to cover in later blog posts). However, this is early days of the blog, so I don’t need much. It’s time to “keep it simple”.

When one is developing cloud code, THREE things need to happen to get the code on the cloud:

- Provision the infrastructure.

- Configure the infrastructure to accept the code.

- Deploy the code to the infrastructure.

For the purposes of the walk-through today, I’m using the Jekyll site that I used to build this blog. But you could use anything that generates static web content.

The infrastructure

For my purposes (this blog site), I only need one resource - an Azure Static Web App. A static web app is a resource that holds and serves the HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and other assets for a web site. It can be any web site - React, Vue, Angular, Svelte, Solid, Qwik, Next, Nuxt, Nest, or any other HTML/JS web framework. You don’t even need a web framework. Use a static site generator like Jekyll (used to generate this site), Hugo, Docusaurus, Hexo, Vuepress, and many more can be used.

You only need the ability to generate the HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and assets for the web site.

Once you’ve deployed the code, the site is globally available and cached at the edge. You can use GitHub Actions to deploy your code automatically - it’s a zero downtime deployment (i.e. the new site doesn’t take over until all the files are in place for the new site).

Once you are ready to go to production, you can upgrade the SKU and add a custom domain without any down time.

There are other good things about Azure Static Web Apps (and we’ll discover them as we go along). For now, let’s look at the three ways to get your code running in the cloud.

Method 1: The CLIs

Some people like to have control, so this method gives me the ability to control exactly what is going on every step of the way. So, let’s take a look at what I need to do to provision, configure, and deploy this site.

Prerequisites

I need a few tools. If you took a look at my last post, you’ll note I have all these tools in my dev container. The links are to the installation page for the tool and don’t include any tooling you need to build your application. If you are deploying a Jekyll site, for example, you need to install Ruby and Jekyll before starting as well. However, since you are already developing code, you’ll have those tools installed.

You will also want to sign in to Azure and select a subscription if you have access to more than one subscription.

Create the resources

All resources are created inside a resource group - a container for related resources, so I have to create one of those first.

az group create -n apps-on-azure -l centralusNow I can easily create a static web app resource:

az staticwebapp create -n apps-on-azure-site -g apps-on-azure -l centralusYou can also use Azure PowerShell and the Azure portal for provisioning the resources.

Configure the resources

The main thing to do here is to configure a staticwebapp.config.json file. This is sent to Azure Static Web Apps to configure the features needed. I don’t actually need anything beyond the basic hosting, so my file is remarkably simple:

{

"navigationFallback": {

"rewrite": "/index.html"

}

}This tells Static Web Apps where the index page that I want to use is located. Check this file into source code control.

Deploy the code with the SWA CLI

To deploy the code, I’m going to use the Static Web Apps CLI. This is one of those “npm” tools, so it’s easy to install in the project:

npm add -D @azure/static-web-apps-cli

npx swa init --yesDon’t forget to add the

package.jsonfile to source code control and ensure thatnode_modulesis added to the.gitignorefile (or equivalent).

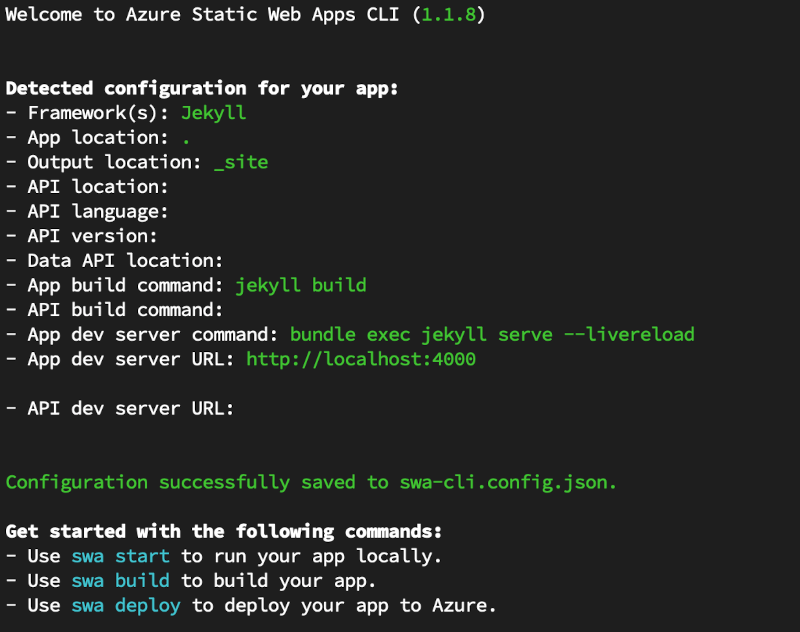

The initialization tries to detect what is application is based on and thus where it can expect the output or distributable files. My build process is bundle exec jekyll build and the files are placed in _site after the build. Check out the output of the swa init command:

Now I can deploy the code:

npx swa login -R apps-on-azure -n apps-on-azure-siteThis prompts me for subscription and tenant information. You can avoid these prompts by setting environment variables before you run the command:

export AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID=`az account show --query "id" --output tsv`

export AZURE_TENANT_ID=`az account show --query "tenantId" --output tsv`However, I find this is too much typing for an infrequent operation. Mostly, I switch over to one of the other methods after I’ve deployed once, so this is definitely an optional step.

Finally, let’s deploy the code:

npx swa build

npx swa deploy -n apps-on-azure-siteThis will build my site and deploy the code to the static web app (downloading the tool that actually deploys the code if necessary). Once the deployment is done, the URL of the site is displayed - I can click on it to view the site.

Method 2: Azure Developer CLI

Now that I know what I need to do with individual steps, I can start to automate the process. The best tool for this is the Azure Developer CLI - an open-source tool maintained by Microsoft that bundles both an infrastructure deployment and a code deployment in one tool.

To use this tool, you need to:

- Write some bicep code to describe your infrastructure.

- Write an

azure.yamlfile to describe the deployment. - Do any code changes necessary to support the infrastructure.

- Run the

azd upcommand to deploy your code.

The nice thing about this method is that you can just run azd up again whenever you make any changes to either the infrastructure or the code. I’ll assume you have installed azd already, but that’s the only pre-requisite here.

Write the infrastructure code

All the infrastructure code is created inside an infra folder at the top level of your project. It consists of a main.bicep file to describe the infrastructure, and a main.parameters.json file to adjust the deployment parameters. Let’s take a look at my main.parameters.json file first:

{

"$schema": "https://schema.management.azure.com/schemas/2019-04-01/deploymentParameters.json#",

"contentVersion": "1.0.0.0",

"parameters": {

"environmentName": {

"value": "${AZURE_ENV_NAME}"

},

"location": {

"value": "${AZURE_LOCATION}"

}

}

}This is relatively straight forward. There is an “environment name” - this is a short name that you choose that allows you to create unique resource names. You’ll also want to specify the region that the resources are deployed in. Static Web Apps supports just five regions (eastus, westus2, centralus, westeurope, and eastasia), so you’ll want to select one of those when prompted.

Now, let’s take a look at the bicep code. I’ve removed all the comments from this code so that it reads well inside the blog, but you should definitely comment your code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

targetScope = 'subscription'

@description('The environment name - a unique string that is used to identify THIS deployment.')

param environmentName string

@description('The name of the Azure region that will be used for the deployment.')

param location string

var resourceToken = uniqueString(subscription().subscriptionId, environmentName, location)

var tags = { 'azd-env-name': environmentName }

resource rg 'Microsoft.Resources/resourceGroups@2024-03-01' = {

name: 'rg-${environmentName}'

location: location

tags: tags

}

module swa 'br/public:avm/res/web/static-site:0.3.0' = {

name: 'swa-${resourceToken}'

scope: rg

params: {

name: 'swa-${environmentName}'

location: location

sku: 'Free'

tags: union(tags, { 'azd-service-name': 'web' })

}

}

output AZURE_LOCATION string = location

output SERVICE_URL string = 'https://${swa.outputs.defaultHostname}'

Let’s walk through this:

- Line 1 - bicep can operate assuming a subscription level deployment or a resource group deployment. I need a subscription level deployment so that I can create a resource group.

- Lines 3-7 - read in the values from the

main.parameters.json- azd will set these for me. - Line 9 - create a unique string based on the subscription ID, environment name and location. I’ll use this if needed to generate a unique name for a resource or deployment.

- Line 10 - create an object to use for tagging the resources I create.

- Lines 12-16 - create a resource group to hold the resources being created.

- Lines 18-27 - create a static web app inside the resource group with the Free SKU, tagged with a specific service name (for deployment).

- Lines 29-30 - output the things I need to know about the deployment.

I’m using a module from the Azure Verified Modules collection here. Azure Verified Modules (or AVM) is a collection of bicep modules that you can use to help configure your resources. You can consider them “batteries included” modules. They generally cover how to deal with diagnostics, resource locks, role assignments, and private networking in a standardized way across all resource types. You should definitely consider using them in your infrastructure projects if you use bicep as they will significantly reduce the size of your bicep code.

Write an azure.yaml file

The azure.yaml file is used by the Azure Developer CLI to link the resources deployed in the infrastructure step to the code that needs to be deployed on them. You need to give each resources that has code deployed to it a unique name and set the azd-service-name tag to that name. In my case, I’ve tagged my static web app with the name web. Let’s look at the azure.yaml file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# yaml-language-server: $schema=https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Azure/azure-dev/main/schemas/v1.0/azure.yaml.json

name: apps-on-azure-blog

services:

web:

project: .

dist: _site

language: js

host: staticwebapp

The web service (at line 5) corresponds to the service name that I specified in the infrastructure section.

Code changes

As in the first method, you will need to create a staticwebapp.config.json file. I’ve copied the same file here in case you are following the instructions:

{

"navigationFallback": {

"rewrite": "/index.html"

}

}Deploy the code with the Azure Developer CLI

Finally, I can deploy my code. First, sign in with the Azure Developer CLI:

azd auth loginAnd then run the end-to-end deployment:

azd upYou are prompted for additional information when running this for the first time (the environment name, subscription, and location). You won’t be prompted for these again. The information is stored in a .azure directory within your project.

Method 3: GitHub Actions

I’ve got my code checked into a GitHub repository, so it would be really nice if I had a GitHub Action that deployed my code whenever I checked into the main branch. There are two potential GitHub Actions I can utilize here:

Of these two, I prefer the Azure Developer CLI method. The Azure Developer CLI method allows me to set up the deployment first (see Method 2 above) and then add the GitHub Action later on. It also handles my infrastructure deployment and can deploy additional resources if necessary. If my code runs into a problem, I can diagnose it outside of the GitHub Actions mechanism, which means I don’t need to use a runner.

The Static Web Apps Deploy method has the advantage that you don’t need to set up a service principal in Entra ID so that your GitHub Action can communicate with Azure. Instead, you need a deployment token that you can retrieve from the Azure Portal. You can also set up the deployment from the Azure portal by linking the GitHub repository to your Static Web Apps resource. In addition, you can automatically deploy preview sites based on pull requests, giving you an automatic mechanism for previewing code before it is merged into production.

So, let’s walk through setting up a GitHub Action using the Azure Developer CLI method.

First, create the .github/workflows directory. This is where the GitHub Action definitions live in your project.

Next, create a workflow in that directory. I called mine deploy-blog.yml:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

on:

workflow_dispatch:

push:

branches:

- main

permissions:

id-token: write

contents: read

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

env:

AZURE_CLIENT_ID: ${{ vars.AZURE_CLIENT_ID }}

AZURE_TENANT_ID: ${{ vars.AZURE_TENANT_ID }}

AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID: ${{ vars.AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID }}

AZURE_CREDENTIALS: ${{ secrets.AZURE_CREDENTIALS }}

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Install azd

uses: Azure/setup-azd@v1.0.0

- name: Install nodejs

uses: actions/setup-node@v4

with:

node-version: 20

- name: Install Ruby

uses: ruby/setup-ruby@v1

with:

ruby-version: '3.1.3'

bundler-cache: true

- name: Build Site

run: bundle exec jekyll build

env:

JEKYLL_ENV: production

- name: Log in with Azure (Federated Credentials)

if: ${{ env.AZURE_CLIENT_ID != '' }}

run: |

azd auth login `

--client-id "$Env:AZURE_CLIENT_ID" `

--federated-credential-provider "github" `

--tenant-id "$Env:AZURE_TENANT_ID"

shell: pwsh

- name: Log in with Azure (Client Credentials)

if: ${{ env.AZURE_CREDENTIALS != '' }}

run: |

$info = $Env:AZURE_CREDENTIALS | ConvertFrom-Json -AsHashtable;

Write-Host "::add-mask::$($info.clientSecret)"

azd auth login `

--client-id "$($info.clientId)" `

--client-secret "$($info.clientSecret)" `

--tenant-id "$($info.tenantId)"

shell: pwsh

env:

AZURE_CREDENTIALS: ${{ secrets.AZURE_CREDENTIALS }}

- name: Provision Infrastructure

run: azd provision --no-prompt

env:

AZURE_ENV_NAME: ${{ vars.AZURE_ENV_NAME }}

AZURE_LOCATION: ${{ vars.AZURE_LOCATION }}

AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID: ${{ vars.AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID }}

- name: Deploy Application

run: azd deploy --no-prompt

env:

AZURE_ENV_NAME: ${{ vars.AZURE_ENV_NAME }}

AZURE_LOCATION: ${{ vars.AZURE_LOCATION }}

AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID: ${{ vars.AZURE_SUBSCRIPTION_ID }}

Let’s go through this file line by line:

- Lines 1-5 dictate when this action will be executed - in this case, either manually or when I push a change to the main branch.

- Lines 7-9 indicate what permissions are required.

- Lines 11-77 are the actual steps needed to deploy the code.

- Lines 13-18 set up the environment for the deployment.

- Lines 20-21 checks out the code.

- Lines 23-35 install tools necessary for the deployment.

- Lines 37-40 build the code for later deployment.

- Lines 42-63 sign in to Azure using the credentials I’ve provided in the environment. There are two versions - one for a service principal and one for federated credentials.

- Lines 65-77 provision the resources, then deploy the code.

Before I can use this action, I need to establish some credentials for Azure in my GitHub repository. These are stored as secrets. Use the following command to establish those credentials:

azd pipeline configThis command will copy your current environment to the GitHub Actions, log into Azure, and store those federated credentials as secrets with the GitHub Action as well. I hope you named your environment the way you wanted to before you ran the command!

The command will ask if you want to push your local changes (say yes) and then it will display the link to the actions. You can (and should) click on the actions link and see if your action was successful.

Clean up resources

If you’ve been following along, you probably don’t want the resources you created to stick around. Even though the Azure Static Web Apps SKU is free, you only have 10 of them and you may want to use it for something else. To clean up the resources, just delete the resource group:

az group delete -n apps-on-azure

azd downEach command will take a couple of minutes. If you do run azd down, make sure you also disable the GitHub Action in your repository and remove the secrets and variables that were stored.

Final thoughts

So, which method should you use?

- For one-off deployments and tweaks to existing resources, I reach for the Azure CLI and associated tools. You wouldn’t stress about using the Azure portal either - it’s a one off - the method is really not important.

- For repeatable deployments and continuous deployments via GitHub Actions (or any other pipeline runner, including Azure Pipelines), I use the Azure Developer CLI. It’s a single command to spin up a development environment that is separate from my production environment, and it’s easy to integrate into GitHub Actions.

I’ve now completed the next step in publishing this blog. In the first step I set up my local environment inside a dev container. In this step, I’ve created my site in the Azure cloud and I am automatically deploying my code to the site when I check in new blog posts. Next time, I’m going to investigate what it takes to go production.

Leave a comment